Hideo Sasaki Designing a Landscape

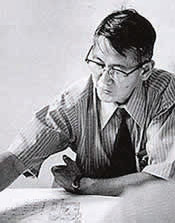

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT HIDEO Sasaki (1919-2000) created the master plan for the Sea Pines Plantation development, bringing to it his signature interdisciplinary approach as well as his philosophy of respecting the natural environment – both revolutionary ideas of his time.

Developer Charles E. Fraser

shared many of these ideas with Sasaki,

which made them an ideal team.

When Fraser commissioned Sasaki’s

newly emerging firm to devise a land

plan for his seaside property, history

was being made. With an impressive

resume and background already established,

Sasaki had served as professor

and then chairman of the department

of Landscape Architecture of the Harvard

School of Design for 18 years.

He created a master plan for a resort

that still serves as a model worldwide.

Developer Charles E. Fraser

shared many of these ideas with Sasaki,

which made them an ideal team.

When Fraser commissioned Sasaki’s

newly emerging firm to devise a land

plan for his seaside property, history

was being made. With an impressive

resume and background already established,

Sasaki had served as professor

and then chairman of the department

of Landscape Architecture of the Harvard

School of Design for 18 years.

He created a master plan for a resort

that still serves as a model worldwide.

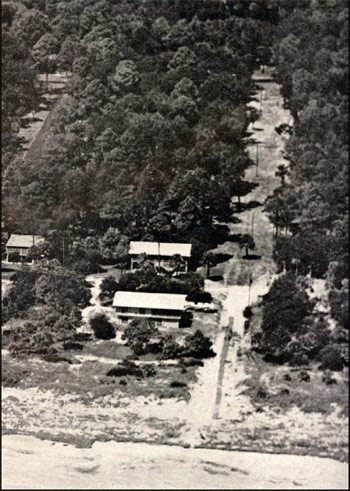

Unlike most other housing and resort developments of the time, Sasaki didn’t force a grid pattern on the seaside property. Instead, his layout of the neighborhood lots and roads was sensitive to the island’s topography, environment and residents’ needs.

This was a broad step away from the regular grid street network that dominated contemporary beach communities in the United States. Instead of plotting out a single row of houses running between the main road and the ocean, Sasaki planned a community where homes were clustered, putting as many as six rows of lots on the ocean side of the main road. Culde- sacs and dead-end roads branch off from the main thoroughfare. And between the houses, there are 50-footwide walkways leading from the row of lots farthest from the beach.

“We call it an interlocking finger

plan,” Sasaki once said of how the

beach front lots were created. “Actually

it’s very similar to the cluster plan

used in Radburn, New Jersey, 32 years

ago.”

“We call it an interlocking finger

plan,” Sasaki once said of how the

beach front lots were created. “Actually

it’s very similar to the cluster plan

used in Radburn, New Jersey, 32 years

ago.”

Radburn was designed in 1928 by Frederick Law Olmsted and was the first garden city in the United States. Olmsted’s plan was to combine the best of the city and the countryside into his design. He focused on using three critical elements: the public realm (streets, sidewalks and small parks), individually owned house lots and open space owned and shared by neighboring residents.

Sasaki cleverly took the ideas from

Radburn and expanded on them to

increase the number of valuable lots.

A home didn’t have to be situated on

the ocean front to enjoy sea breezes,

sweeping views and quick access to

the beach.

Instead of allowing the man-made environment of a resort to dominate Sea Pines, Sasaki let the natural coastal ecology take center stage. In fact, the plan called for a low density of houses. These homes were designed to be clustered on half of the Sea Pines property while setting aside acres for beaches, golf courses, parks, wildlife preserves, tidal marshes and other open spaces. About 1,400 acres were protected through open space covenants, including the more than 600 acres that became the Sea Pines Forest Preserve.

The plan Charles Fraser and Hideo Sasaki developed for Sea Pines Plantation served as the seed that grew into a world-class destination resort, the first of its kind in the United States.

Even before its completion, the 2nd International Urban Design Conference cited it for exceptional merit in 1957. And in 1959 it won an award for excellence in design by the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Sasaki went on to design many

other noteworthy projects, including

Euro Disneyland in Paris France, Boston

Waterfront Park in Massachusetts

and the Denver Skyline Urban Renewal

Project.

Throughout his career, Sasaki insisted

that his profession not imitate or

follow its sister arts but instead form a

dynamic bridge with architecture, civil

engineering and urban planning. His

approach in creating balanced urban

designs revolutionized and brought

a modern approach to not only the

projects he worked on but also to his

profession, leading and shaping the

future of landscape architecture.